Early 2020 Columbia River salmon forecasts come to light and sockeye returns are just about the only highlight in what could be another dismal season Leave a reply

We’re still months away from getting our first glance at 2020 salmon forecasts but the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) fishery managers have already dished out some early signals of what lies ahead.

“It is so early yet in the process but I’m guessing we will be looking at conservative measures especially from what we saw (lower than expected salmon returns for some stocks including Columbia River coho) in 2019,” said Wendy Beeghly, the head WDFW coastal salmon manager.

“What alarms me is the ongoing poor ocean conditions and it was supposed to be on an upcycle,” Beeghly said. “This makes me somewhat pessimistic than what I had originally thought a month ago.”

For the most part the picture on the wall isn’t very pretty but there could be a bright spot along the 1,243-mile stretch of the Columbia River.

The computer generated “paper fish” predictions released last week by WDFW calls for 246,300 sockeye, which is up considerably from 2019’s forecast of 94,400 (downgraded in July of 2019 to 62,800) and an actual return of 63,222.

If the 2020 sockeye forecast becomes reality it would rank as the eighth largest return dating back to 1980 but only a third of the record run in 2014 that totaled 614,180.

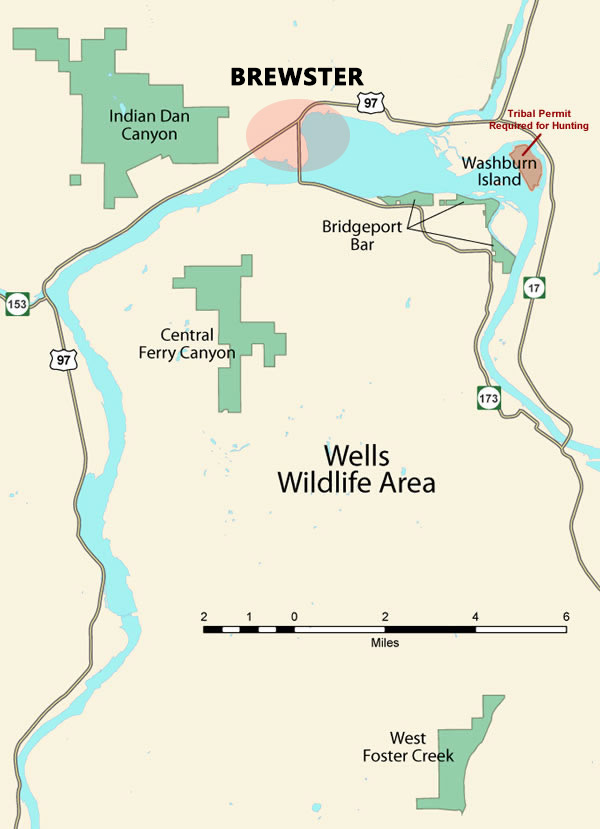

Of those 201,800 sockeye are destined for the thriving Okanogan River system (74,500 was forecasted in 2019 and 54,300 actually returned) where many will linger in the Brewster Pool, a popular early-summer deep-water salmon fishing location on the Upper Columbia, before migrating to upstream spawning grounds.

Sockeye migrate from its confluence just below Chief Joseph Dam, north into its headwater lakes in British Columbia that is known for its notoriously warm water and changing river flow patterns in the summer.

The poor sockeye runs in 2019 can be attributed to the impact of disastrous 2015 drought and hot water that killed off a lot of adult fish. The puny run that survived to spawn led to fewer juvenile fish in recent years, which was then further negated by predation downstream and poor ocean conditions (the worst seen in the last two decades) from “The Blob.” This warm-water phenomenon in the northern Pacific raised water surface temperatures and sat firmly from 2013 until dissipating somewhat last year.

The summer-migrating sockeye are learning to adapt their upstream migration timing in recent years therefore most fish returns are peaking sooner than later in the summer. Over the past few decades they would peak by early July but it’s shifted to late June and has resulted in higher sockeye survival in recent years.

The Lake Wenatchee sockeye run – the second largest of the Columbia River sockeye component – is 39,400 (18,300 was forecasted in 2019 with an actual return of 7,900). The lake is a highly popular mid- to late-summer sport salmon fishery. The annual escapement goal is 23,000 sockeye at Tumwater Dam and only then a lake fishery can be considered.

Another very important Columbia salmon is the spring chinook – a return that fuels the fire in early spring fisheries when anglers are coming out of the winter doldrums – with a 2020 forecast of 135,800 (down from 157,700 forecast in 2019 but up from an actual return of 109,808; and 157,500 in 2018 and 176,642). The 2020 springer forecast is the lowest prediction dating back to 1999.

The important upriver spring chinook-bound total is 81,700 (down from 99,300 in 2019 and an actual return of 73,1010; and 166,700 in 2018 and 115,081).

On the Oregon side, the 2020 Willamette River spring chinook run isn’t rosy with 40,800 predicted, up a from 2019’s forecast of 40,200 and an actual return of 27,292.

Other less palatable spring chinook forecasts are the Lower Columbia tributaries, which are also taking a hit in 2020.

The Cowlitz is 1,400 (1,300 forecasted in 2019 and actual return of 1,600; and 5,150 in 2018 and 4,000); Kalama is 1,000 (1,400 and 1,000; and 1,450 and 2,300); and Lewis is 1,300 (1,500 and 1,000; and 3,700 and 3,200). On Oregon side, the Sandy is 5,200 (5,500 and 3,260; and 5,400 and 4,733).

The 2020 spring Chinook forecast for the Cowlitz River is the second lowest since 1980.

The 2020 spring chinook forecast for the Kalama is about half of the recent 10-year average run size of 1,900; and the Lewis is about 75 percent of the recent 10-year average run size of 1,700.

There is a yearly 30 percent buffer on the Columbia River spring chinook mainstem fisheries that protects against overfishing. In 2019 a closure was issued below Warrior Rock on the mainstem to protect spring chinook destined for Cowlitz and Lewis, and it’s likely this could happen again in 2020.

Spring chinook returns to tributaries above Bonneville Dam for the most part of down as well in 2020. The Wind is 2,000 (2,800 forecasted in 2019 and an actual return of 1,600); Drano Lake aka Little White Salmon is 4,600 (5,600 and 3,600); Klickitat is 1,800 (1,100 and 400).

The 2020 forecast for the Wind is about one-third of the recent 10-year average return of 5,900; Drano is about half of the recent 10-year average return of 10,800; and Klickitat is similar to the recent 10-year average return of 1900.

The Upper Columbia summer chinook return is 38,300 (up from 36,340 in 2019 and actual return of 34,619; and well below 67,300 in 2018 and an actual return of 42,120). Fishing for summer run kings also known as “June Hogs” was closed in 2019 except for a small area in the Upper Columbia above Wenatchee that opened later in the summer.

WDFW fishery managers also laid out general summaries with no forecasts for fall chinook and coho and how they fared in 2019.

2019 Preliminary Returns

• Adult fall chinook return was predicted to be 349,600 fish.

• Preliminary return is slightly above the forecast.

• Bright jack return appears to be improved over 2018. Tule jack return appears to be slightly improved over 2018.

2020 Outlook

• Bright stocks should be similar to the 2019 preliminary return.

• Tule stocks should be similar to the 2019 preliminary return. This stock is the main driver in ocean salmon fisheries.

• Ocean conditions between 2015 and 2019 were among the worst observed during the last 21 years and are likely continuing to have a strong influence on the fall chinook return in 2020.

Columbia River Coho

• 2019 preliminary return is about 30 percent of the preseason forecast of 611,300.

• Coho jack return to the Columbia River is less than 50 percent of the recent three-year average.

The sport-salmon fishing season setting process begins on Feb. 28 when WDFW unveils most of the salmon forecasts during a public meeting at DSHS Office Building 2 Auditorium, 1115 Washington Street S.E. in Olympia.

Subsequent meetings are March 16, North of Falcon public meeting at Lacey Community Center; March 19, North of Falcon public meeting in Sequim; March 23, Pacific Fishery Management Council public hearing at Westport; March 25, North of Falcon public meeting at WDFW Mill Creek office; and March 30, North of Falcon public meeting at Lynnwood Embassy Suites, 20610 44th Avenue West in Lynnwood.

The Pacific Fishery Management Council will adopt final salmon fishing seasons on April 5-11 at the Hilton Vancouver, 301 West 6th Street in Vancouver, WA.

Oldest salmon derby gets underway

The Tengu Blackmouth Derby – the oldest salmon derby that began prior to and shortly after World War II in 1946 – is held on Sundays 6 a.m. to 11 a.m. starting Jan. 5 through Feb. 23 on Elliott Bay at the Seacrest Boathouse (now known as Marination Ma Kai) in West Seattle.

In previous years, the derby started in October when Area 10 opens for winter hatchery chinook. However, this year’s non-retention of chinook delayed the event to coincide with the Jan. 1 opener. Last year, the derby was cancelled when WDFW decided to shutdown Area 10 just a few weeks after it began.

What makes the derby so challenging is the simple fact blackmouth are scarce around the inner bay during winter months.

The derby is named after Tengu, a fabled Japanese character who stretched the truth, and just like Pinocchio, Tengu’s nose grew with every lie.

In a typical derby season, the catch ranges from 20 to 23 legal-size chinook and has reached as high as 50 to 100 fish although catches have dipped dramatically since 2009. The record-low catch was four fish in 2010, and all-time high was 234 in 1979.

The last full-length season was 2017 when 18 blackmouth were caught and a winning fish of 9 pounds-15 ounces went to Guy Mamiya. Justin Wong had the most fish with a total of five followed by John Mirante with four fish.

It has been a while since a big fish was caught in the derby dating back to 1958 when Tom Osaki landed a 25-3 fish. In the past decade, the largest was 15-5 caught by Marcus Nitta during the 2008 derby.

To further test your skills, only mooching is allowed in the derby. No artificial lures, flashers, hoochies (plastic squids) or other gear like downriggers are permitted. The membership fee is $15 and $5 for children age 12-and-under. Tickets will be available at Outdoor Emporium in Seattle. Rental boats with or without motors are available from 7 a.m. to 11 a.m.

Dungeness crab fishery extended

The Dungeness crab season along the east side of Whidbey Island (Marine Catch Areas 8-1 and 8-2) will remain open daily through Jan. 31 – originally it was scheduled to close after Dec. 31.

WDFW indicates crab abundance can support an additional in-season increase to the harvest shares. Managers made the decision to extend the season to offset a closure that occurred between Oct. 23 through Nov. 28 while crab abundance was assessed.

Elsewhere some sections of northern Puget Sound and Hood Canal are also open daily now through Jan. 31. They are Area 9 between the Hood Canal Bridge and a line from Foulweather Bluff to Olele Point (Port Gamble, Port Ludlow) and the portion of Marine Area 12 (Hood Canal) north of a line projected due east from Ayock Point.

Sport crabbers are reminded that setting or pulling traps from a vessel is only allowed from one hour before official sunrise through one hour after official sunset.

Other areas open daily through Dec. 31 are Marine Area 4 east of the Bonilla-Tatoosh line; Marine Area 5 (Sekiu); Marine Area 6 (East Juan de Fuca Strait); Marine Area 7 (San Juans, Bellingham, Gulf of Georgia); Marine Area 9 (Admiralty Inlet).

Crabbers must have a Puget Sound Dungeness crab license endorsement and record Dungeness crab retained on a Catch Record Card through Dec. 31, but aren’t required to have them when crabbing in Jan. 1-31 in Areas 8-1 and 8-2 and the open sections of Area 9 and 12. However, a valid shellfish or combination license is required. The 2019 winter catch cards must be returned to WDFW by Feb. 4.